The spycraft might have been straight out of a Russian playbook, however the sport first started with a stroke of pure luck on the a part of US-based Soviet spooks.

Unexpectedly, in 1979, a former Chicago cop — a religious and conservative household man — walked right into a Soviet enterprise in New York that was famously a entrance for Cold War intelligence operatives. Robert Hanssen, who’d jumped from the Windy City police power to the FBI simply three years earlier, provided handy over top-secret particulars to the GRU, the Soviet army intelligence group.

For cash.

His data was good — so good that it could finally result in the executions of a minimum of three US belongings. It cemented a ruthlessly environment friendly, 22-year relationship between Hanssen and his handlers, “possibly the worst intelligence disaster in US history,” in response to the fee later established to research it.

At the centre of the stunning betrayal was a person who appeared woven from the straight-laced cloth of counterintelligence backroomers, a person who rubbed colleagues the mistaken approach however appeared however appeared wholly dedicated to the job and to his nation. Hanssen lived in suburban Virginia together with his spouse and 6 kids, socializing with the identical greatest pal from highschool, unfailingly attending Mass and even trying to recruit others to affix him in Opus Dei, a corporation inside the Catholic Church identified for its airs of ultra-devotion and thriller.

That thriller, nonetheless, would pale compared to the furtive and lethal actions into which Hanssen plunged himself. He was lastly discovered in 2001, arrested in one of many suburban parks he’d so innocuously used as a drop location — his legislation enforcement legacy perpetually in tatters, his household and buddies horrified. Instead of having fun with retirement in picturesque Virginia, Hanssen was relegated to the Supermax in Florence, Colorado, locked away with probably the most harmful and notorious of American criminals.

There, on Monday, he was discovered useless in his cell, an inglorious finish to an ignominious life.

But Hanssen’s legacy of treason stays almost unequalled virtually a quarter-century after his arrest.

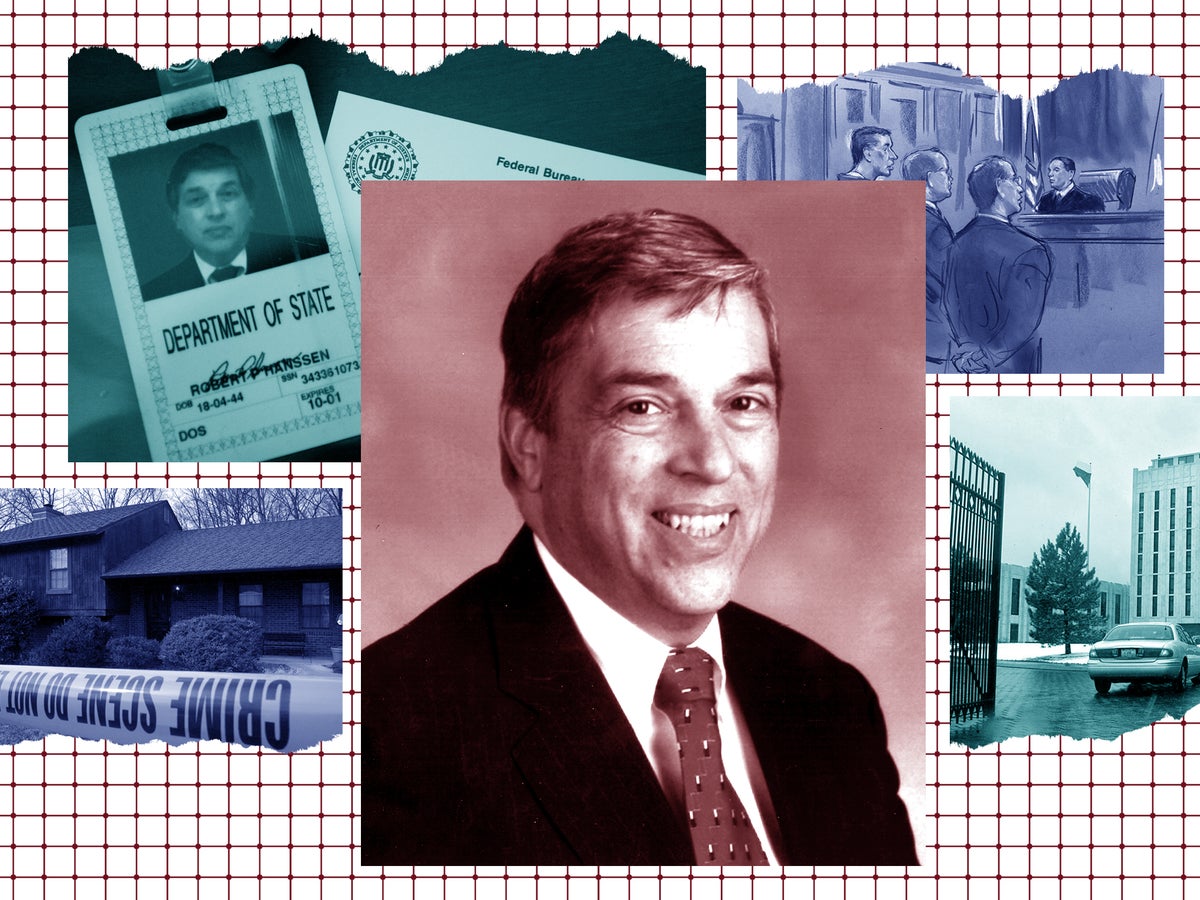

In this artist depiction, U.S. Attorney Randy Bellows, proper, addresses the courtroom through the sentencing of convicted spy Robert Hanssen

(William Hennessy, Jr.)

His pedigree ought to have precluded him from his historic position of traitor, however it additionally completely positioned him to tug it off. Raised in Chicago by a cop father, Hanssen first labored briefly as a CPA earlier than becoming a member of town’s police power — and was despatched straight to work in counterintelligence. He utilized unsuccessfully to the NSA, then tried his hand with the FBI and made it; by 1979, he’d moved to New York together with his younger household and was working within the FBI’s counterintelligence division.

That’s when he made contact with the Soviets on the places of work of Amtorg, a buying and selling firm established in 1924 by the USSR that was identified for staffing members of the GRU.

“The information Hanssen turned over to the GRU was sensational, one of the most guarded secrets of both the FBI and the Central Intelligence Agency,” writes David Wise in his 2002 e-book Spy: The Inside Story of How the FBI’s Robert Hanssen Betrayed America. “Hanssen gave away no less than the identity of TOPHAT — the most important US intelligence source inside the GRU.

“From his access to the FBI’s files, Hanssen was able to identify TOPHAT as the bureau’s code name for Dimitri Fedorovich Polyakov. At the time, Polyakov had been passing secrets to the United States for seventeen years. He was considered by Washington as an gent of supreme importance.

“Hanssen had a chilling reason for his action; he wanted to turn in Polyakov to the GRU before the Russian might learn his identity and reveal it to the FBI,” Wise wrote. “He had to be well aware that his information would probably result in TOPHAT’s execution — that was the whole point.”

According to the 2002 Webster fee, which was fashioned to evaluation FBI safety applications following Hanssen’s devastating leaks, he would later declare that his motivation was financial: the strain of supporting a rising household in New York City on an insufficient Bureau wage. His purpose was to ‘get a little money’ from espionage after which ‘get out of it.’” During this preliminary interval of espionage, he was paid about $20,000, it reported.

As Hanssen was spying from inside the FBI, nonetheless, one other Russian asset was spying from inside the CIA — Aldrich Ames. He, too, disclosed Polyakov’s identification, and TOPHAT was executed in 1986, the Webster fee wrote.

FBI agent Robert Hanssen, who spied for Russia for 20 years discovered useless in supermax jail cell

(FBI)

“Hanssen passed three batches of secrets to the GRU,” Mr Wise writes in Spy. “In his first approach, he disclosed that the FBI was bugging a Soviet residential complex. He also turned over a list of suspected Soviet intelligence officers … He communicated with the GRU through encoded radio transmissions and through one-time pad, an unbreakable cipher system favored by the Russians. But of the various secrets Hanssen passed to the GRU, none compared to his betrayal of TOPHAT.”

By 1981, whether or not burdened by guilt or concern after being transferred to FBI headquarters in Washington DC, Hanssen reduce off contact with the Soviets — and confessed to his spouse, lawyer and a priest, the Webster fee reported.

Hanssen’s spouse, Bonnie, knew the priest by means of Opus Dei, and the clergyman initially inspired the FBI agent to show himself in to authorities — earlier than calling Hanssen later to say that, as an alternative, he might flip his ill-gotten cash over to the Church, Wise writes. He informed his spouse he’d stopped spying, and he or she believed him, by all accounts.

But it wasn’t lengthy earlier than he was again at it.

In 1985, simply 9 days after he’d been transferred to a discipline supervisory place within the Soviet Counterintelligence Division in New York, “he wrote to a senior KGB intelligence operator to inform him that he would soon receive ‘a box of documents [containing] certain of the most sensitive and highly compartmented projects of the U.S. Intelligence Community,’” the fee reported.

“Hanssen asked for $100,000 in return for the documents (he would receive $50,000), and he warned that, ‘as a collection’ the documents pointed to him. Hanssen had particular concerns about his safety,” the fee continued.

“I must warn of certain risks to my security of which you may not be aware,” Hanssen wrote to the Soviets. “Your service has recently suffered some setbacks. I warn that Boris Yuzhin . . . , Mr. Sergey Motorin . . . and Mr. Valeriy Martynov . . . have been recruited by our ‘Special Services.’”

According to the fee, the opposite embedded spy — Ames, of the CIA — “gave the Soviets the same information about the three Soviet defectors around the same time as Hanssen. Two of the defectors were executed; the other was sentenced to fifteen years hard labor.”

Hanssen was accruing wealth and savvy, trying to modernize Soviet spies’ methods, as he handed some 6,000 paperwork and 26 laptop disks to his handlers, which finally modified from GRU to KGB — utilizing aliases listed in an affidavit that embrace “Ramon Garcia” and “Jim Baker.”

The data he handed alongside “detailed eavesdropping techniques, helped to confirm the identity of Russian double agents, and spilled other secrets,” AP reported. “Officials also believed he tipped off Moscow to a secret tunnel the Americans built under the Soviet Embassy in Washington for eavesdropping.”

Hanssen is believed to have enriched himself by $1.4m — and diversified his compensation as time wore on, lamenting to his handlers that it was arduous to spend money with out arousing suspicion.

“Perhaps some diamonds as security to my children and some good will so that when the time comes, you will accept by [sic] senior services as a guest lecturer,” he wrote in a single evening, Wise reviews in Spy.

Drop Site: Package recovered at a drop web site containing $50,000 money left by Russians for Hanssen

(FBI)

“Because Hanssen had suggested a few diamonds might be welcome, the KGB obliged with one in September 1988,” Wise writes, detailing how a gem price $24,720 was left for the FBI agent below a bridge in northern Virginia.

“A few months later, at Christmas, he received a second diamond valued at $17,748. For Hanssen, diamonds had the virtue of being small and therefor easily concealed,” Wise writes. “The cash that kept rolling in from Moscow was getting to be bulky and more difficult to hide, especially in a house that he shared with a wife and six children.”

Hanssen, in the meantime, was flying by means of the ranks of the FBI.

He left the Soviet Analytical Unit in May 1990 when he was promoted to the Bureau’s Inspection employees.

“Among other duties, Hanssen was charged with assisting in the review of FBI legal attaché offices in embassies across the globe. Hanssen’s Soviet handlers offered their congratulations on his promotion: ‘We wish You all the very best in Your life and career,’” the fee detailed. “Having assured Hanssen that their communications mechanisms would remain in place, the Soviets advised him: ‘[D]o Your new job, make Your trips, take Your time.’ Hanssen’s espionage continued after he joined the Inspection staff.

“At the end of his tour on the Inspection staff in July 1991, Hanssen became a program manager in the Soviet Operations Section of the Intelligence Division at Headquarters, a unit designed to counter Soviet espionage in the United States.”

He was, basically, tasked with investigating himself — ostensibly ferreting out traitors whereas committing the last word treason personally.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and Gorbachev’s resignation, Hanssen “decided to disengage from his espionage activity, he claims, because of feelings of guilt,” the fee reported.

He unsuccessfully and briefly tried to re-establish contact in 1993 however didn’t start his third interval of espionage till 1999, when he complained to the Russians about cash issues.

“At the time, Hanssen was ‘running up credit card debt,’ some of which he had rolled into a home mortgage during two refinancings; some of his six children were in college; and ‘financial pressures’ were creating (in a phrase Hanssen adopted during a debriefing) an ‘atmosphere of desperation,” the fee reported. “Hanssen has claimed that his mortgage payments had grown so high that he ‘was losing money every month and the debt was growing.’ Consequently, he set a ‘financial goal’ for himself: obtain $100,000 from the Russians to pay down his debt.”

It was a suburban drop throughout this new spy stage that may in the end be the agent’s undoing.

Ames had been unmasked as a spy in 1994, however US intelligence businesses have been getting more and more suspicious of, and angered by, their nemesis’ continued success at getting delicate data. They couldn’t determine the place the leak was, and focus centred for years, wrongly, on a veteran CIA officer.

It would later end up that officer had, at one level, lived on the identical road as Hanssen and even attended the identical church. But after the FBI got here into possession of a recording of a 1986 dialog between a KGB operative and the suspected mole, it turned clear that CIA veteran was not the speaker.

Analysts who’d labored with Hanssen not solely acknowledged his voice but additionally a phrase he’d been identified to make use of — and the case broke large open.

“In January 2001, Hanssen, who was then under suspicion, was transferred from the State Department to FBI Headquarters so that he could be closely monitored,” the fee reported. “Shortly thereafter, Hanssen would later claim, he came to believe that a tracking transmitter had been placed in his car. Despite these concerns, he went to another drop.”

That drop was on an atypical winter Sunday in 2001. Hanssen had, identical to on each different Sunday, attended Mass together with his household on 18 February, after which he frolicked together with his greatest pal earlier than dropping the Chicago man on the airport. Hanssen then drove to Foxstone Park in Vienna, simply minutes from his residence, the place the unobtrusive 56-year-old — now a grandfather — hauled a plastic rubbish bag sealed with clear tape from his automotive.

He took off for the park, then returned empty-handed — solely to seek out armed brokers ready to arrest him.

Hanssen had delivered to the ultimate drop an encrypted letter on a disk, addressed to “Dear Friends” and signed “Your friend, Ramon Garcia.”

It learn: “I thank you for your assistance these many years. It seems, however, that my greatest utility has come to an end, and it is time to seclude myself from active service. . . . My hope is that, if you respond to this . . . message, you will have provided some sufficient means of re-contact . . . . If not, I will be in contact next year, same time same place. Perhaps the correlation of forces and circumstances will have improved.”

Later in 2001, Hanssen pleaded responsible to fifteen counts of espionage and conspiracy in change for the federal government not looking for the loss of life penalty. He was sentenced to life in jail with out the opportunity of parole, a sentence that ended on Monday in Colorado when the 79-year-old was discovered unresponsive in his cell.

For a person whose life was constructed upon secrets and techniques — protecting them, uncovering them, and promoting them for revenue — Hanssen died with quite a lot of of his personal. He informed authorities following his arrest that his motivation had been monetary; in a 2000 letter to the Russians, nonetheless, he “added, dubiously, that he had made his decision to become a spy as a teenager, inspired by the autobiography of Kim Philby, the Soviet mole inside British intelligence,” Wise writes in Spy.

He remained a person of thriller, dwelling modestly whereas amassing ill-gotten wealth, immersing himself in faith and morality whereas promoting deadly secrets and techniques that condemned and endangered different human lives. Many near him discovered it immensely arduous to reconcile the opposing features of Hanssen’s life following his shock arrest.

“I believe he was seriously religious and a serious spy,” his former FBI boss, Tom Burns, says in Spy. “Maybe a diagnosis would find him totally bipolar, able to segment different parts of his life. Parts that to all appearances were a contradiction.”

Another pal from the State Department, Ron Mlotek, places it in a different way within the 2002 e-book.

“Although Mlotek did not doubt Hanssen’s faith, he thought he had answered the wrong calling,” Wise writes.

“’He should have been a priest,’ Mlotek said. ‘I think everyone would have been better off. The whole world would have been better off.’”

Source: www.unbiased.co.uk